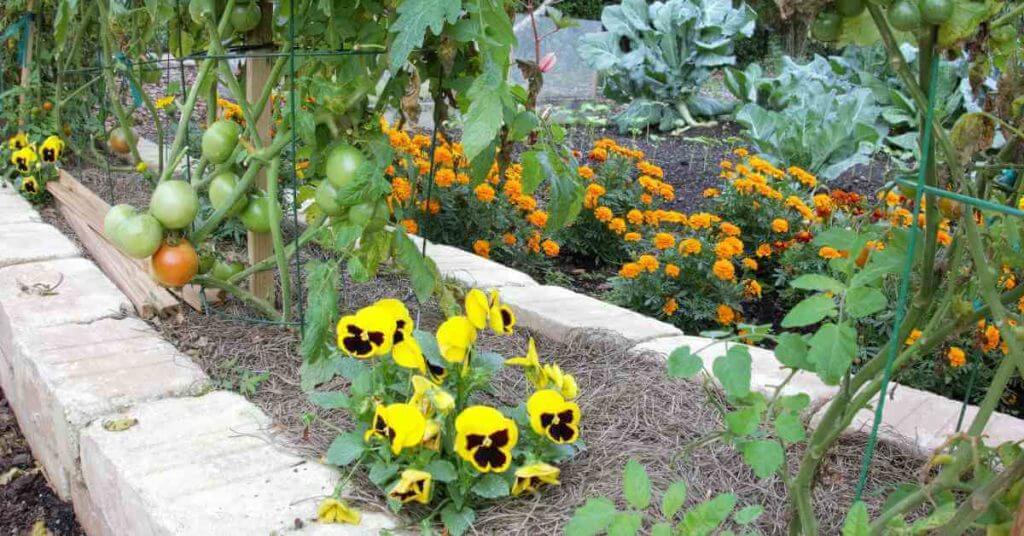

Companion Planting Chart For Fruits

A companion planting chart for fruits, showing which plants help fruits, which are helped by fruit plants, and which to avoid.

If you’re wondering whether the beef you eat is nourishing your body or quietly sabotaging it, you’re not alone.

While beef and most red meat have been considered bad for the heart and cardiovascular health, science is now revealing the opposite. Beef and red meat are full of healthy fats, proteins, and vitamins missing from most people’s diets.

The question remains about what beef to eat: grass-fed or grain-fed. Is grass-fed beef simply a marketing myth, or is it really that much better than the grain-fed store stuff?

Having dedicated many months trying to find out this answer myself, this article will overview everything you need to know about the differences between grass-fed and grain-fed beef, from its nutritional profiles to its environmental impacts, to help you understand exactly what you should be looking for in your beef.

While only a small percentage of cattle can officially be labeled as “grass-fed” (estimates put it around 5% of the US beef supply), it’s important to note that most cows, regardless of their final diet, spend a significant portion of their early lives eating grass. In fact, for much of their initial development, the diets of grass-fed and grain-fed cattle are nearly identical.

Cows begin their lives nursing on their mother’s milk for the first six to eight months, where they remain close to their mothers and transition to pasture grass as they are weaned.

For the next eight months to a year, all cattle—whether destined to be grass-fed or grain-fed—spend their days in open pastures, eating a natural diet of grasses, hay, and other foraged plants.

Around the one-year mark of a cow’s life is when the differences between grass-fed and grain-fed cattle take different paths. For grass-fed cows, the pasture isn’t just a temporary stop—it’s their lifelong home. They’ll continue to roam and graze freely on open fields for another two years or so, feeding on a natural diet of grass until they reach their ideal weight.

This slower, more traditional approach to raising cattle emphasizes their connection to the land, producing a leaner beef often described as having a richer, more natural flavor.

Grain-fed cattle, however, take a very different path. After their time on pasture, they are moved to large-scale facilities called confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

While almost all beef starts its first year grazing on pasture grass, grass-fed and grain-fed cattle begin to diverge at the end of the first year.

Whereas grass-fed beef will continue to graze on grass and hay for the remainder of their lives, grain-fed cattle will be moved to confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Here, their lives shift dramatically as they transition from grazing to a high-calorie diet of grains.

A whopping 95% of cattle in America are grain-fed, meaning they spend their final six or so months on a diet of cereal grains like corn, oats, and barley.

These feedlots are designed to speed up weight gain, ensuring they reach market size much faster than their grass-fed counterparts. This efficiency has its benefits (particularly for the bottom line of the farmers, and thus us as consumers) but also raises questions about animal welfare, environmental impact, and the quality of the beef produced.

Historically, all beef produced until the 1940s was from grass-fed and finished cattle before the introduction of feedlots. During the 1950s, considerable research was done to improve the efficiency of beef production, giving birth to the feedlot industry where high-energy grains are fed to cattle as a means to decrease days on feed and improve marbling.

Most of what you buy in the supermarket will be grain-fed, although for how long varies tremendously among suppliers.

As if finding the best quality beef wasn’t difficult enough, grass-fed and grain-finished beef further complicates matters.

Grass-fed and grain-finished beef can be a little misleading, as even feed-lot beef starts its first year on grass, and can technically be called grass-fed.

As a result, many grain-fed beef suppliers may advertise as grass-fed and grain-finished, which, although technically correct, misleads the consumer into thinking a special effort went into grass-feeding when it did not.

There is no regulatory oversight here, so you must ask for exactly how long the beef you are buying was grain-fed, and hope they are telling the truth. For reference, the cheapest beef fed with grains as soon as they can are fed grains for an average of six months, depending on how quickly they can reach their target weight.

If you’re concerned about the quality of your beef, always look for 100% grass-fed beef, and stay away from marketing scams of “grass-fed grain-finished”.

Research results show that grass-fed beef is higher in total nutrients, phytonutrients, antioxidants, key fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, protein, and amino acids compared to grain-fed beef, but let’s take a deeper dive into the specifics.

Among the most significant differences between grass-fed and grain-fed beef is their fatty acid profile, which affects a vast array of nutrition and health aspects.

This study by The Weston A. Price Foundation studied the nutritional differences between samples of grass-fed beef from a supermarket in Southern Maryland and grain-fed beef from a farm in Western Maryland.

Using gas chromatography, a method used to separate and quantify individual fatty acids, they found that the largest differences between the two samples were the total concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), and the balance between the omega-3 and omega-6 forms of these fatty acids.

Grass-fed tallow (rendered beef fat) had 45% less total PUFA, 66% less omega-6 linoleic acid (an inflammatory fat), and four times more omega-3 alpha-linolenic acid (a healthy fat).

The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids, an increasingly important ratio for health, was over sixteen for the grain-fed tallow but only 1.4 for the grass-fed tallow. The typically claimed “grass-fed and grain-finished” beef can be anywhere between these values, depending on how long it was grain-fed for.

Whatever the ratios, beef tallow is not a rich source of polyunsaturated fatty acids, with only 3.45% in grain-fed and 1.9% of the total in grass-fed.

In fact, the levels of PUFA found in grass-fed tallow are similar to that found in the coconut products that dominate the traditional diets of Pacific Islanders, who have been extensively studied and shown to be free of heart disease. Saturated stearic acid was also found to be 36% higher in grass-fed beef.

Thus, in equally fatty cuts of beef, there would be a higher content of saturated fatty acids in the grass-fed beef. In many traditional diets where the fattiest cuts and the fat itself were sought out, intake of these saturates would likely be considerably higher.

In terms of vitamins, several studies suggest that grass-based diets elevate precursors for Vitamin A and E, as well as cancer-fighting antioxidants such as glutathione (GT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity as compared to grain-fed contemporaries.

This website has a great table comparing the vitamin differences between grass-fed and grain-fed patties.

Like most other mammals, cows become less efficient at converting their food into fat and muscle as they age. To counteract this aging process, grain-fed cattle receive a higher-energy diet to quickly reach their ideal weight.

As a result, grass-fed beef contains less fat and more vitamins and antioxidants than grain-fed beef. Grain-fed beef, on the other hand, has more fat and is less lean (many BBQ’ers prefer a fattier cut when grilling meat),

Cattle kept in feed lots also increases the risk of diseases spreading, so antibiotics are sometimes used to prevent infections (a practice called subtherapeutic use).

It may seem strange how the taste of beef can vary, after all, it’s all cow, right? In truth, the diet an animal receives has a significant effect on taste, the reason why grass-fed beef has some unique flavors.

Grass-fed beef has a distinct flavor that many describe as “earthy,” “gamey,” or slightly “mineral-like.” The taste is often influenced by the cow’s diet, which includes a variety of grasses and forages. Regional differences in forage can create subtle variations in flavor, the reason why some special breeds of cattle pasture-raised in special areas command such a high price.

While some (particularly me) love its bold, robust flavor, others find it less appealing compared to the richer taste of grain-fed beef, especially if you’re used to eating fattier beef cuts.

Grass-fed beef is typically leaner because cows raised on pasture consume a lower-calorie diet and take longer to grow. The lower fat content results in a firmer, chewy texture, which some consumers appreciate for its “cleaner” mouthfeel. For those who prefer their meat softer, however, grass-fed beef simply requires lower heat and gentler techniques to preserve its tenderness.

However, because it has less intramuscular fat (marbling), it can dry out more easily if overcooked, hence why many prefer fattier grain-fed cuts, particularly for BBQing.

Anyone who’s ever attempted to buy grass-fed meat knows that it usually comes with a pretty significant price increase. In Costco, for example, grain-fed beef can be bought for between $7 to $12 per pound, depending on the cut, compared to $10 to $15 for the same grass-fed cuts from a farmers market.

It’s pretty easy to see why the price difference: grain-fed beef is cheaper and easier to produce at scale, requires significantly less acreage to raise per cow, reaches maximum slaughter weight much more quickly, and grain production is typically subsidized in many countries.

As a result, you can expect to pay anywhere between 30-100% more for grass-fed beef, depending on where you buy. You will likely also have to invest some time in finding well-priced grass-fed meat from smaller farm stores – grass-fed beef is difficult to find in most chain supermarkets.

For those serious about finding affordable grass-fed meat at a comparable price to supermarket beef, there is only one real option. Buying a quarter or half-cow from an independent farm is the only way to obtain quality meat at a competitive price, although it comes at a hefty upfront cost (despite the $/lb ratio often being lower than store prices), and you’ll need a few deep freezes to store it. For reference, a half cow can easily feed a family of four for a year.

Despite Bill Gates’ constant fear-mongering about meat production contributing to climate change, particularly his push for questionable vaccines to reduce cow methane emissions, the truth is that beef production, a practice humans have engaged in for thousands of years, does not inherently harm the planet.

Much of the concern revolves around methane, a key component of the biogenic carbon cycle—the natural process by which carbon moves between the atmosphere, plants, animals, soil, and water. Here’s how it works:

In well-managed systems, this cycle can be nearly carbon-neutral, especially if the pastureland sequesters more CO2 than the methane emitted.

Grass-fed, pasture-raised systems that embrace regenerative agriculture principles actively sequester carbon in the soil. Healthy, biodiverse pastures act as carbon sinks, pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere and storing it underground. When managed correctly, these systems can make cattle farming not just carbon-neutral, but potentially carbon-negative.

In contrast, the grain-fed, feedlot-based system that dominates in many countries is far from carbon-neutral. It relies on monocropped grains, fossil fuels, deforestation, and other environmentally harmful practices, which critics often conflate with all beef production. They fail to recognize the potential of sustainable, grass-fed systems to minimize emissions and improve environmental outcomes.

The real issue is that governments subsidize grain corporations, which skew the natural greenhouse gas cycle and exacerbate climate change. Meanwhile, taxpayers foot the bill, funding the environmental damage caused by industrial beef production and the subsequent attempts to mitigate its effects.

This is a win-win for corporations but a lose-lose for taxpayers. A smarter solution would be to subsidize pasture-raised farmers, which would reduce greenhouse gas emissions and eliminate the need for costly carbon taxes.

For corporations the current system works perfectly – they profit from cheap, subsidized grain, scale up production in CAFOs, and offload environmental cleanup costs onto taxpayers. For taxpayers, it’s a raw deal: they fund a system that harms the environment, drives small farmers out of business, and undermines long-term food sustainability.

The choice between grass-fed and grain-fed beef goes beyond taste or price—it impacts your health, the environment, the skin, and the sustainability of our food systems. While grain-fed beef is often more affordable, it can be lower in quality and come with hidden environmental costs.

Grass-fed beef offers a healthier alternative, packed with omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins, and antioxidants that support overall well-being. By choosing grass-fed, you’re making a healthier choice for yourself.

Beyond health, your decision also supports a more sustainable food system. Grass-fed beef, especially from regenerative farms, helps improve soil health, reduce carbon emissions, and promote biodiversity. By supporting these systems, you’re contributing to a more ethical and sustainable approach to beef production.

In short, opting for grass-fed beef benefits both your body and the planet. Small actions, like choosing quality meat or supporting local farmers, can make a big difference.

The choice between grass-fed and grain-fed beef goes beyond taste or price—it impacts your health, the environment, and the sustainability of our food systems. While grain-fed beef is often more affordable, it can be lower in quality and come with hidden environmental costs.

Grass-fed beef offers a healthier alternative, packed with omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins, and antioxidants that support overall well-being. By choosing grass-fed, you’re making a healthier choice for yourself.

Research results show that grass-fed beef is higher in total nutrients, phytonutrients, antioxidants, key fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, protein, and amino acids compared to grain-fed beef.

Grass-fed beef is typically leaner because cows raised on pasture consume a lower-calorie diet and take longer to grow. The lower fat content results in a firmer, chewy texture, which some consumers appreciate for its “cleaner” mouthfeel. For those who prefer their meat softer, however, grass-fed beef simply requires lower heat and gentler techniques to preserve its tenderness.

A companion planting chart for fruits, showing which plants help fruits, which are helped by fruit plants, and which to avoid.

Here are the 5 best companion plants for strawberries, and how each will compliment each other for healthier and more lucrative strawberries.

Pinterest Instagram Youtube Pinterest Instagram Youtube Jump to: Have you ever stopped to consider what’s really in the water flowing from your tap? For many of

Discover the benefits of organic gardening with our guide on how to make compost tea. This simple process enriches soil, promoting plant health.

Here is a companion planting chart for herbs, showing which herbs work great together, and which should be avoided.

Here is a comprehensive and easy to follow companion planting chart for vegetables, based on available scientific literature and trial and error experience.