How To Test Soil pH – The 3 Main Ways

Learn how to test soil pH with these 3 easy techniques, whether at home or from a professional laboratory.

Diving into the world of gardening can be a mix of excitement and curiosity, especially when you stumble upon the concept of companion planting. This age-old practice, rooted in the wisdom of cultures past, is all about planting different crops together for mutual benefit.

At its core, companion planting embodies the spirit of polyculture and permaculture, championing biodiversity and sustainable gardening practices that work with nature, not against it.

But how do you navigate this symphony of plant relationships? Is there a science to it, or is it all just garden folklore? As you’ll discover, companion planting might not be an exact science and much of what you hear about companion planting is likely overrated, but there are real and tangible benefits from adopting the right forms of companion planting.

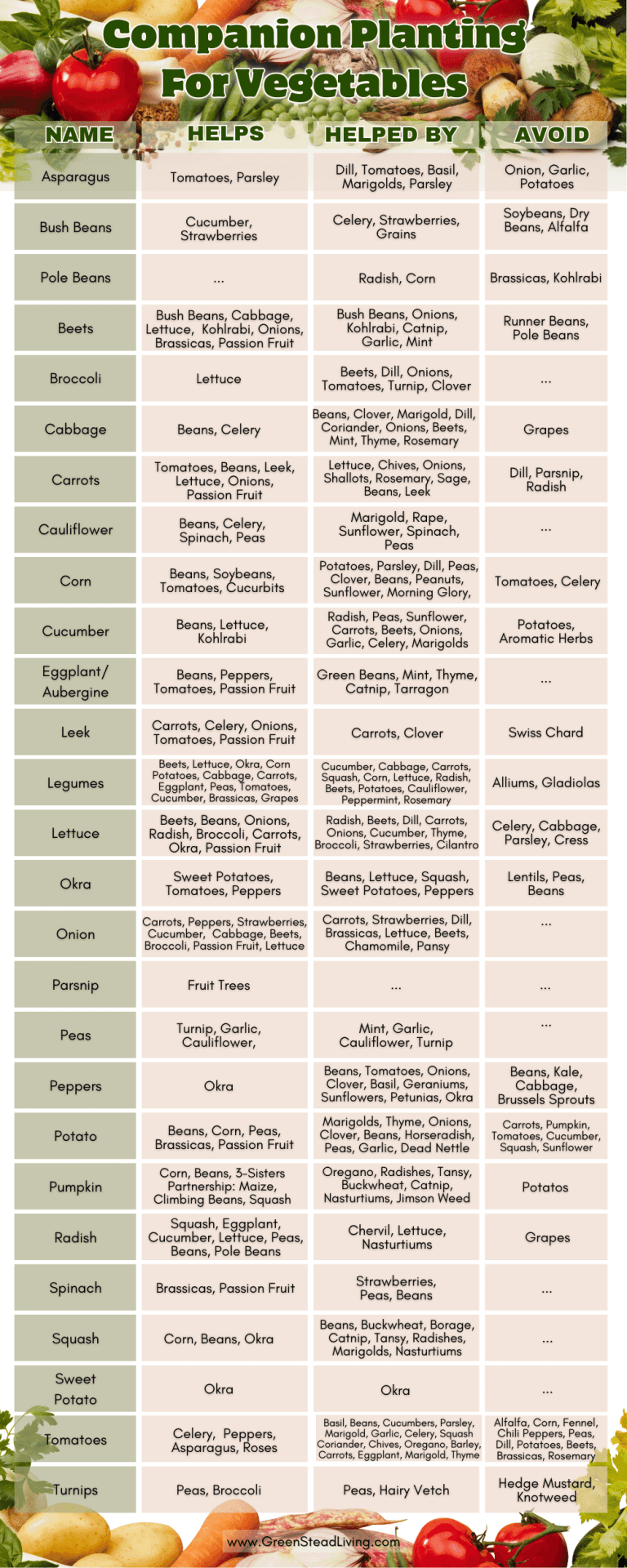

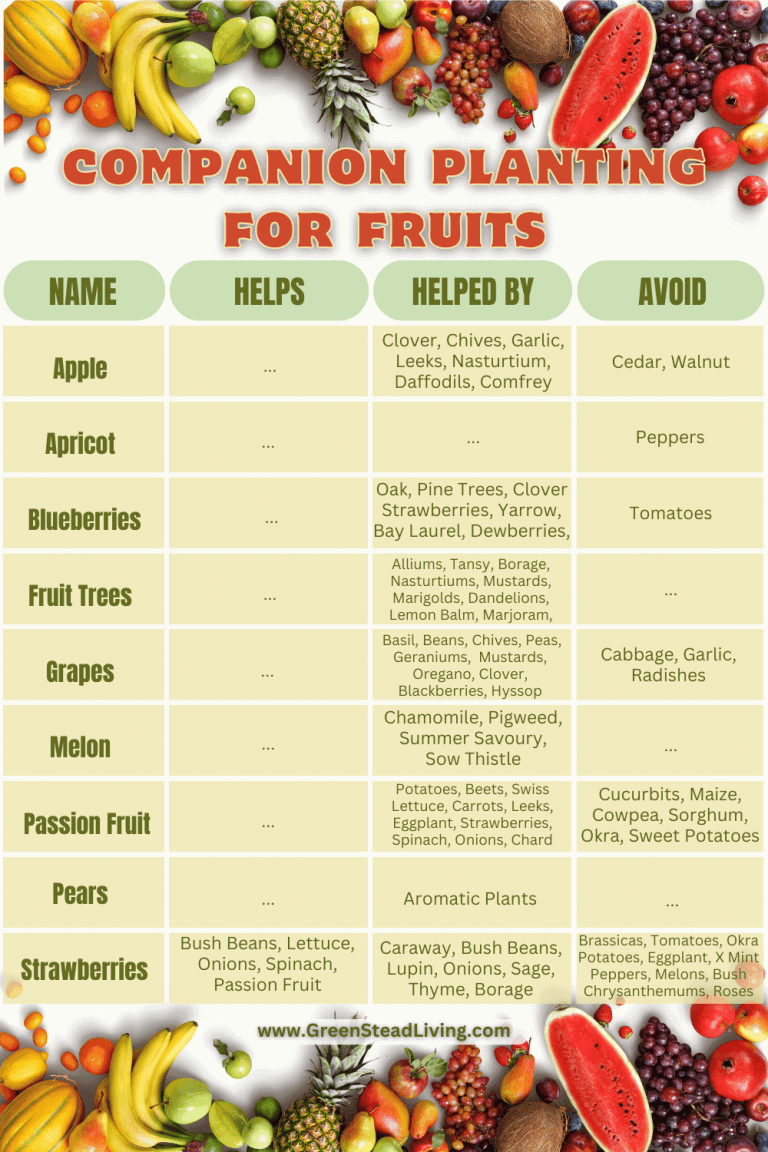

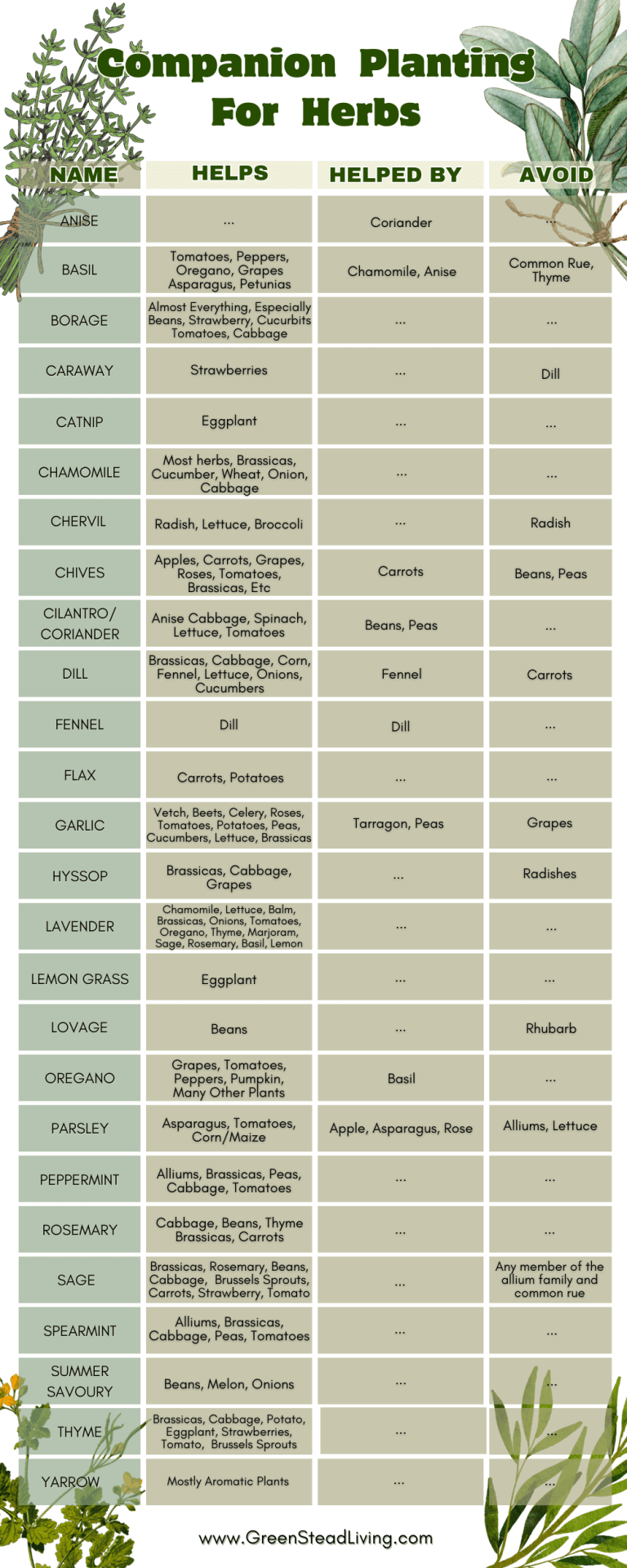

From the nitrogen-fixing abilities of legumes to the pest-distracting power of marigolds, every plant can have a role to play. Yet, it’s not just about the benefits. Some plants might as well be feuding neighbors, so knowing who to plant next to whom is key to a peaceful garden.

This beginner’s guide to companion planting will take you through the ins and outs, the whys and hows, and the dos and don’ts. More importantly, we’re going to cut through the myths to avoid you wasting your time.

Companion planting is a gardening practice where different crops are planted close together for mutual benefits, namely pest control from harmful bugs and insects, pollination, maximizing the use of space, and increasing crop productivity.

Companion planting is a form of polyculture, an agricultural approach where multiple crop species are grown together to enhance productivity, pest control, and biodiversity. It is also widely used in the growing movement of permaculture, where gardens are designed to work with nature, rather than against it, by creating spaces that are sustainable, productive, and good for the planet.

Certain plants are known to complement each other by utilizing the soil differently. The most common example is “The Three Sisters”, a form of companion planting used by various Indigenous peoples in North America that involves the interplanting of three essential crops: corn (maize), beans, and squash.

With The Three Sisters, corn acts as a natural trellis for the beans to climb, maximizing space and reducing the need for artificial supports. In return, the beans will fix nitrogen from the air into the soil, enriching it and providing essential nutrients for all three plants. As a result, the squash can thrive and spread out along the ground, shading the soil with its broad leaves, which helps retain soil moisture and suppress weeds.

The beauty here is that each plant helps the others to thrive, which in turn allows itself to thrive, creating a circular and synergistic relationship that maximizes the benefits of the whole to a greater level than the sum of its parts. This is what we wish to achieve when planting our own garden crops.

It is true that companion planting is not an exact science and successful companion plantings can vary in different areas. While some studies demonstrate the benefits of companion planting, such as clover reducing the number of cabbage root flies laying eggs next to cabbages by almost 30%, much of companion planting is based on anecdotal observations and trial and error.

Fortunately, plenty of anecdotal evidence spanning many decades adds some weight to these claims. Mosquito ferns, for example, have been successfully used for at least a thousand years as companion plants for rice crops.

The truth is, however, that most of the companion planting information available online is largely overrated.

For example, many sources advise against planting tomatoes and peppers together because they belong to the same species, compete for the same nutrients, and are susceptible to the same diseases.

Although this is accurate, and thus they are not considered companions, does it mean they can’t be grown together successfully? Absolutely not. In fact, like many others, I consistently harvest both tomatoes and peppers every year. You just need to ensure you leave enough space for both to thrive and keep an eye out for early signs of pests and diseases to ensure they don’t spread.

So when you read that you should never plant “X” with “Y”, take it with a pinch of salt. Although they may not be companions on paper, it does not mean they cannot be grown successfully with a little bit of thought.

Then there is the problem of dealing with the overwhelming number of factors involved in successfully grown plants, such as differences in local climates, what zone you’re in, and your specific locale (how much sun your plot gets, etc). There are countless possible combinations of these variables, meaning there will never be a one-size-fits-all approach for any companion suggestion.

While one gardener in sunny Arizona, US, might benefit from companion plants that are drought-tolerant and have similar water needs to tomatoes, like oregano and basil, another in Suffolk, UK, with generally cooler temperatures and more rainfall, might include leafy greens like spinach, which benefit from the cooler, more moist conditions.

That is why it is essential that companion planting be approached as a trial-and-error method. Companion planting charts, such as the one below, are an excellent start, but you must remain observant and tweak based on your own circumstances. And if you want to plant tomatoes and peppers together, go ahead; just ensure you leave enough space and avoid the potential problems shown later in this article.

To put the significance of companion planting into perspective, compare it to owning ten houses in a row where you’re responsible for making sure each tenant is as happy as possible. In an ideal world, each tenant would live in 5 acres of space where neighbors are not a concern, but in the reality of our limited-sized garden plots, we have to do the best we can with the space available.

Naturally, some tenants will not like each other for a myriad of reasons, so you try to move them to opposite ends with as much space between them as possible.

Conversely, some tenants will become best friends with their neighbors, so you would try to put them closer together.

Most tenants, however, will remain somewhere neutral; perhaps neighbor A dislikes neighbor B’s loud music on a Sunday night, but since they are kind enough to take their bins out for them on Monday morning, they tolerate them overall. Thus they might not be considered ideal companions, but the positives outweigh the negatives, and they find a way to work together the best they can.

So companion planting is about making the most of the space you have. Much of the following list is in ideal conditions that will likely never exist in real life. Cabbage and tomatoes are not advised to grow together, but they are both in demand, so all we can do is give our best effort to provide the conditions for them to thrive, such as by moving them further apart.

Additionally, the effects of “companion” planting are often so minimal that other factors—such as care, soil quality, and weather—will significantly outweigh any benefits or drawbacks of planting certain plants together. This means that, unless you are a professional gardener who has optimized all conditions, companion effects will be less significant than focusing on the basics of sunlight, soil quality, and watering.

Some of the claimed benefits of companion planting are indeed unproven at best, and likely overplayed. I commonly hear that planting chilies near tomatoes makes your tomatoes taste spicier, and planting basil can also enhance their flavor.

There is no evidence to back this up, nor can I see any mechanism that could facilitate this. It is more likely that the observed benefits are from other indirect mechanisms, such as pest control, that result in a healthier (and thus tastier) tomato plant more generally.

The real and tangible benefits of companion planting can be condensed down to five key mechanisms:

Some plants are known for improving soil health and nutrient value. A prime example is the symbiotic relationship between legumes, like clover, and their plant neighbors, such as grasses.

Legumes are equipped with a unique ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, thanks to the symbiotic bacteria housed in their root nodules, a process that converts nitrogen from the air into nitrogen compounds that are readily available in the soil for use by nearby plants.

When clover and grasses are grown together, the nitrogen fixed by the clover’s root nodules becomes a direct, natural fertilizer for the grasses while reducing the need for artificial fertilizers. As a result, the grasses can produce more protein, vital for their growth and development, leading to more robust and vigorous plants.

Beans are another common example where they fix nitrogen in the soil to benefit other crops like corn. In return, corn stalks serve as natural trellises for bean vines, demonstrating mutual support and nutrient exchange.

Note, however, that such nitrogen-fixing plants only release this stored nitrogen when the plant decomposes, and the benefits of improved soil health won’t be realized until the next growing season.

A second key benefit of companion planting is pest control, which can occur through multiple mechanisms.

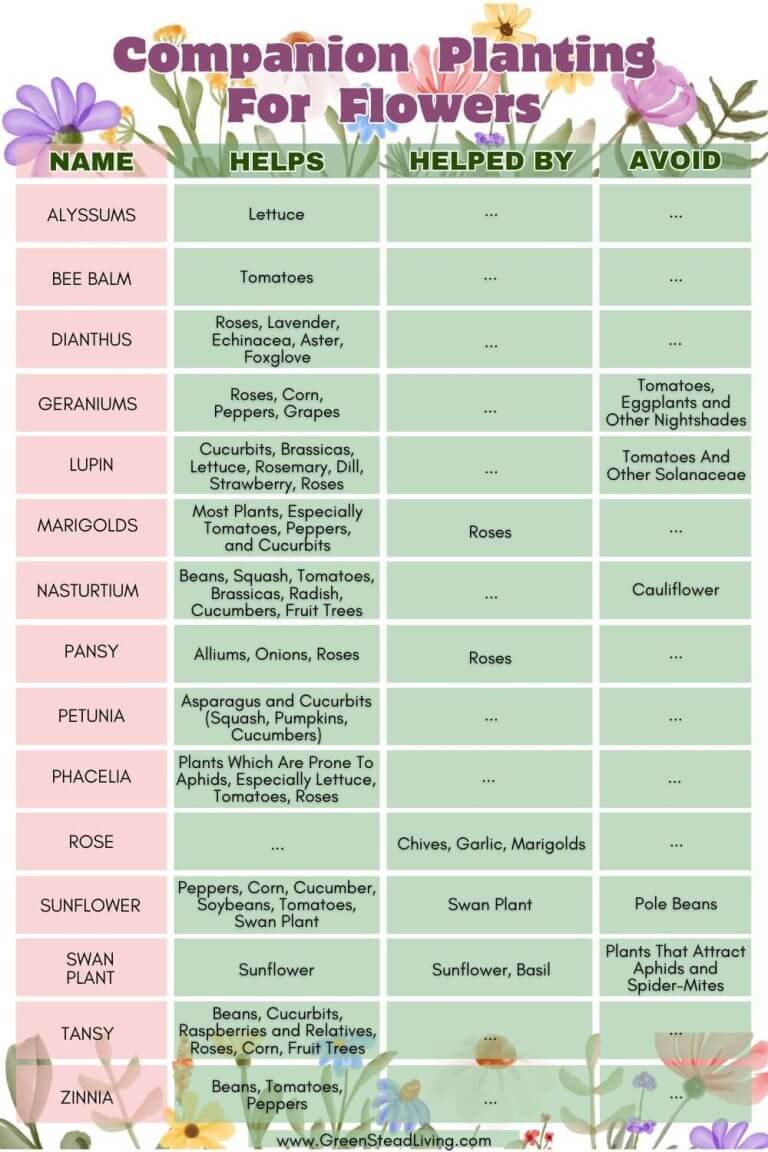

Some plants use trap cropping to act as a sacrifice for your main plant. Nasturtium, for example, attracts caterpillars that like to feed members of the cabbage family (brassicas) by sacrificing themselves as a tasty distraction for caterpillars. By planting near vegetables, the eggs of the pest are laid on the nasturtiums instead of your prized vegetables.

Some plants operate by host-finding disruption, where pests are disoriented by “decoy” plants and are less likely to find your main crops.

Pests tend to look for plants to infest in steps. First, they smell the plant, which makes them want to land on it. If the plant is all by itself, the pest easily lands on it because it’s the only green spot near the smell. But if the pest lands on the wrong plant, it quickly realizes its mistake, flies off, and tries another plant. If it keeps landing on the wrong plants too many times, it gets frustrated and leaves the area.

Flying pests such as aphids, bugs, and beetles, are also far less successful if their host plants are surrounded by other plants or even green-colored decoy plants. For example, the smell of the marigolds is thought to deter aphids from feeding on neighboring plants

A well-known tactic among gardeners is pairing onions and carrots because each repels the other’s pests. It’s widely believed that the strong scent of onions wards off carrot root flies, while carrots’ aroma discourages onion flies.

Some companion plants are used for their weed-suppressing abilities. They do this through a process known as allelopathy, which refers to the process by which certain plants release chemicals into the environment that inhibit the growth of surrounding plants.

Rye, for example, is useful as a cereal crop that is commonly used as a cover crop to suppress weeds in agriculture. Rye releases phytotoxic compounds from its roots when it breaks down, acting as a natural herbicide and enhancing its utility in agricultural systems for weed management and soil improvement.

Some crops thrive under the protective shelter of other plants, whether acting as shade or a windbreak.

Plants that can thrive under the shelter of other plants, often referred to as understory or shade-tolerant plants, have adapted to grow in lower light conditions typically found beneath the canopy of larger plants. Many garden vegetables fall into this category, such as leafy greens (kale, spinach, lettuce), herbs, root vegetables (carrots, beets, and radishes), and many varieties of peas and beans.

Plants and vegetables that are tall and have large leaf areas are known to be sensitive to constant winds, such as corn, tomatoes, peas, and peppers. Plants that act as natural windbreaks, therefore, are often valuable companion plants for these.

Typically, trees and shrubs such as evergreens and hedges are used for windbreaks, but for those with smaller plots who want to maximize their vegetable planting space, artichokes, tall perennial herbs, and sunflowers can provide partial wind protection.

Without pollination, you won’t be getting any fruit or vegetables, no matter how much you plant. I first learned this with tomatoes, not understanding that fruits and vegetables are only produced once the “male” pollen enters the “female” flower. Without pollination, your plants will just produce flowers and then die at the end of the season, without yielding any fruit or vegetables.

By increasing pollination efficiency through companion planting, you can indirectly increase the yield and quality of your crops.

Pollination also encourages genetic diversity within plant populations, making plants more resilient to diseases, pests, and changing environmental conditions. Pollinators are equally important for biodiversity and functioning ecosystems more broadly, essential for the reproduction of many wild plants and insects such as bees.

Marigolds are often used as pollinators, especially for tomatoes, as they attract bees and other pollinators with their bright blooms. Lavender, borage, sunflowers, and zinnias are also great companion plants for many vegetable staples.

Unfortunately, not all plants get on well with their neighbors, and while various plants prove excellent companions for some plants, they might act as nightmare neighbors for others.

Ancient authors from classical Greece and Rome were aware over 2000 years ago that some plants were toxic to others. Theophrastus, for example, noted that the bay tree and cabbage plant weakened their precious grapevine significantly.

Fortunately, most plants tend to produce at least some benefit to others, with a couple of straightforward common sense exceptions.

The first principle to avoid detrimental plant combinations is ensuring that each of your plants has sufficient root space. Tomatoes, for example, should not be planted too close to other deep-rooted plants such as beets, eggplants, and potatoes (members of the same Solanaceae family) as they are all deep-rooted and heavy feeders and will outcompete each other.

This does not mean that you cannot place tomatoes next to potatoes, you just need to leave sufficient space so they don’t compete. Instead, you could put some shallow-rooted plants nearby, such as spinach or radish, and make more efficient use of your space by utilizing nutrients in different layers of your soil.

Remember that even as seeds, you need to sow in consideration for fully grown plants. Follow the spacing requirements on the seed packet or look up online.

The second key consideration is pests. Tomatoes, for example, are susceptible to the same pests as corn (such as the corn earworm), so planting these two together increases the chances of both becoming infected.

Of course, this same principle applies to planting tomatoes next to each other (or any other plant for that matter). Ideally, you would not plant plants of the same variety together, but this is not ideal, especially for large gardens where harvesting would end up very complicated. Hence there is a compromise between ideal conditions and practicality. But by minimizing how many of the same species of plants you plant close together, you can offset the chances of diseases and pests spreading.

Understanding which plants to keep apart can be as crucial as knowing which to grow together for a healthy, productive garden. It’s always a good idea to research specific companion planting guidelines for the plants in your garden, as regional differences and specific plant varieties can influence compatibility.

There is also a third category of unsuitable companion plants – allelopathic plants – plants that release chemicals into the environment that inhibit the growth of surrounding plants.

Beans, which include both pole and bush varieties, are known to be inhibited by all members of the onion family (including garlic, leeks, and shallots) due to allelopathic (toxic to certain plants) compounds that they release. I have only found this effect when they are planted too close together, however.

Sunflowers and Walnut trees are also commonly cited allelopathic plants, although I have had success using sunflower plants as shady companions for other vegetables, so long as I give them enough space.

Many reports state that these effects are overstated, and I personally haven’t had any troubles with what I could perceive as allelopathic damage. Some experts claim that this is only a problem in poor soil conditions, so for those with raised beds or amended soil, the issue shouldn’t be significant.

If this sounds confusing, don’t sweat too much. The effects are usually pretty minimal and if some plants don’t work for you, that’s a lesson you can use next season.

Companion planting is not an exact science, and successful companion plantings can vary in different areas. However, companion planting charts such as the one below can offer a good starting point.

Companion planting isn’t just about putting plants together; it’s about creating a garden community where everyone gets along and helps each other out. It’s a natural way to boost your garden’s health and productivity without relying on chemicals. Plus, it’s pretty simple to start.

Whether you’ve got a green thumb or you’re just starting, trying out companion planting will teach you a lot about nature’s connections. Just be patient and accept that some ideas simply won’t work.

Think of it as a mix of trial and error and paying close attention to what your garden tells you. Different spots have different needs, so what works for one gardener might not work for you. But that’s part of the fun – figuring out the best matches for your garden’s unique vibe.

By choosing plants that play nice together, you not only get a happier garden but also take a step towards a more sustainable world. So go ahead, experiment with companion planting, and watch your garden grow into a thriving ecosystem of its own.

Companion planting is a gardening practice where different crops are planted close together for mutual benefits, namely pest control from harmful bugs and insects, pollination, maximizing the use of space, and increasing crop productivity.

With The Three Sisters, corn acts as a natural trellis for the beans to climb, maximizing space and reducing the need for artificial supports. In return, the beans will fix nitrogen from the air into the soil, enriching it and providing essential nutrients for all three plants. As a result, the squash can thrive and spread out along the ground, shading the soil with its broad leaves, which helps retain soil moisture and suppress weeds.

Tomatoes, for example, should not be placed near other deep-rooted plants such as beets, eggplants, and potatoes (members of the same Solanaceae family) as they are all deep-rooted and heavy feeders and will outcompete each other.

Tomatoes are also susceptible to the same pests as corn, the corn earworm, so planting together increases the chances of both becoming infected.

Similarly, beans, which include both pole and bush varieties, are inhibited by all members of the onion family (including garlic, leeks, and shallots) due to allelopathic (toxic to certain plants) compounds that onions release.

Learn how to test soil pH with these 3 easy techniques, whether at home or from a professional laboratory.

The ultimate guide to reap the benefits of no-dig gardening, complete with a step-by-step guide on building your own.

Growing microgreens at home with trays is the easiest and cheapest method to begin growing a substantial amount of your own food.

Learn how to make beef tallow at home with this step-by-step guide. Perfect for cooking and skincare, this method ensures pure, long-lasting tallow.

The differences between grass-fed vs. grain-fed beef are vast. From nutritional value to taste and sustainability, here are the key differences.

Learn how to grow tomatoes from seed by starting indoors, transplanting carefully, and providing ample sunlight and water for best results.